Hamilton the Poet

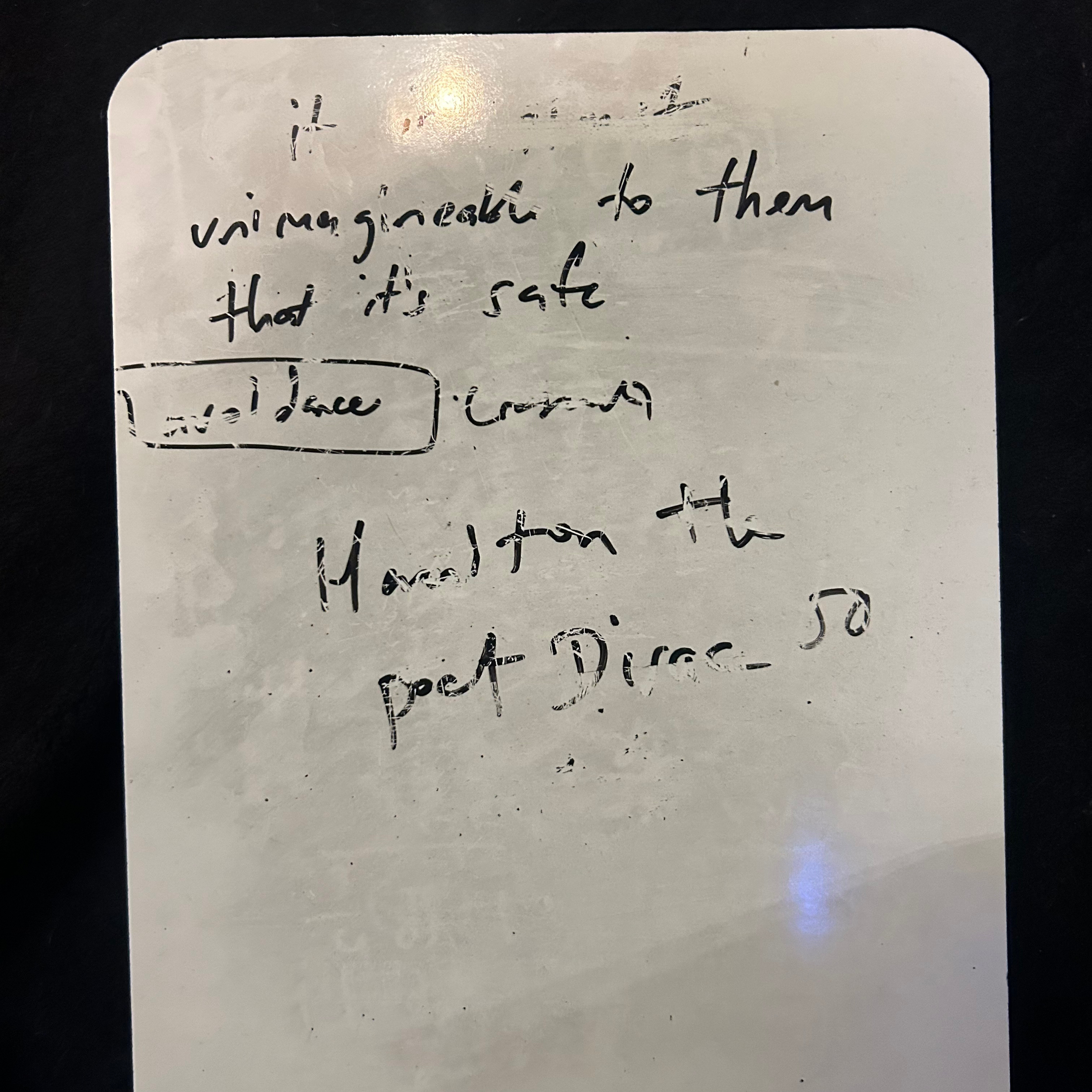

I came across a line in a biography of Paul Dirac. It went like this: “During his mathematics degree, Dirac encountered the ideas of William Hamilton, the nineteenth century Irish mathematician and amateur poet.” I underlined the sentence and went to bed. I woke up the next morning and could not get it out of my head that he called Hamilton an amateur poet. I thought about it for weeks. Then I wrote it on a whiteboard.

I think I can finally erase this. Plus I need the whiteboard.

Paul Dirac is one of the architects of quantum mechanics and won the Nobel Prize for it. William Hamilton invented the Hamiltonian, a mathematical object that transfixed Dirac in college. The Hamiltonian acts on so-called state vectors of the universe and is, suffice to say, one of the pillars of quantum mechanics. Calling Hamilton an amateur poet reminded me of the time New York Times food critic Craig Claiborne called cookbook author Michael Field a former piano player.

I’ve seen Hamilton’s name before. In Peter Woit’s brilliant book Not Even Wrong, he dedicates many sentences to Hamilton, some of which I’ve underlined. None of them are about poems.

I had to get to the bottom of this. “This” led me to Robert Perceval Graves’s Life of Sir William Rowan Hamilton: Selections from his Poems, Correspondence and Miscellaneous Writings.

His poems!

Hamilton was enough of a poet that the word was included in the title of his 1882 biography. So was Hamilton a good poet or an amateurish one?

Here is his poem about botany. It’s called Botany:

‘O, do not say that with less loving heart

The beauty of a flower is gazed upon,

If once the eye enact the scholar's To that wood- wandering honey-laden Art, Which, with the bee, doth every flower explore, And gather, out of many, one sweet lore, From blossom'd bank or bower slow to depart. The sense of beauty need not sleep, though mind, With its own admiration, wake, and yield Its proper joy — with feeling thought entwined: Considering the lilies of the field, Whose rare array, and gorgeous colouring Outshone the glory of the Eastern King

At this point I should confess something: I do not know much of anything about poetry. I do not know the difference between a good poem, a great poem, and a disastrous poem. I get intimidated whenever a poem starts with “O” or “Lo.” I have read Robert Pinsky’s The Sound of Poetry and Mary Oliver’s A Handbook of Poetry — both absolute gems — and still don’t understand anything. What I have decided is that it’s extremely adorable that Hamilton was sitting in an observatory reformulating the ideas of Newton while also having equally zealous feelings about poetry:

Many pleasurable feelings inspire me to write to you; yet the immediate motive is a sort of indignation, excited by reading extracts from Crashaw's poems, in the first number of the Church of England Quarterly Review (January, 1837) which I have only now received. Be so complaisant as to turn to page 189; and although no inducement will I trust be needed to prevail upon you to read lovingly the poem to the Name of Jesus, I beg that you will, after reading it, endeavour, for my sake, to read as much as you can of the poem preferred by the reviewers, the version of the Twenty-third Psalm, than which, according to them, can anything be more beautiful or graceful! I answer, " Yes, anything!" (William Hamilton, letter to Aubrey De Yere, 1837)

I guess I will defer to William Wordsworth on this matter. William Wordsworth was a great poet, or so history says. He told Hamilton he should stick to mathematics.